The Commonwealth Environmental Water Holder’s (CEWH) Science Program funds the Flow Monitoring, Evaluation and Research (Flow–MER).

We would like to acknowledge the Kurnu-Baakandji Peoples, the Traditional Owners of the Warriku (Warrego) and Baaka (Darling) Rivers and surrounds. Thank you for sharing your Country and knowledge of the land, water and life with us. We pay respects to Elders past and present.

Traditional Paakantyi Language of the Kurnu-Baakandji Nation used in this article. (L. A. Hercus – Paakantyi Dictionary), additional to learnings from interacting with community members and the Junction of the Warriku (Warrego) and Baaka (Darling) Rivers Selected Areas Culture Advisor.

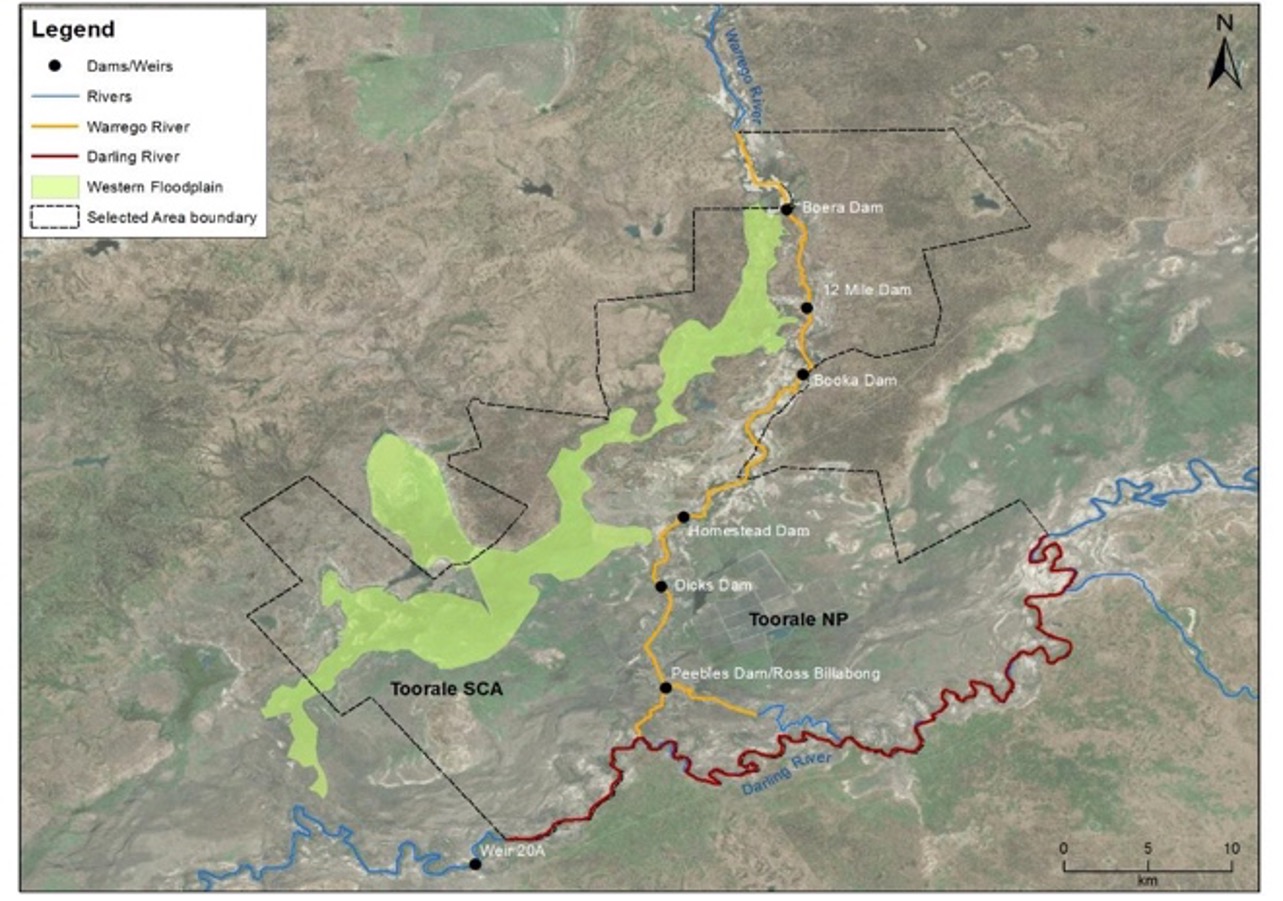

For the last decade the CEWH has funded river and floodplain-wetland monitoring and research in the Warriku-Baaka (Warrego-Darling) Rivers and catchment (Figure 1). This work is part of the larger Flow – Monitoring, Evaluation and Research (Flow–MER) program that spans the entire Murray-Darling Basin.

The Warriku-Baaka (Warrego-Darling) Selected Area (Selected Area) is located around 80 km south-west of Bourke in northwestern NSW and is contained within the boundary of the Toorale National Park and State Conservation Area (Figure 1). The Baaka (Darling) River catchment drains the north westerly portion of the MDB. Most of its tributaries (Macquarie, Castlereagh, Namoi, Gwydir, Macintyre and Condamine-Balonne Rivers) drain the Great Dividing Range in northern New South Wales and southern Queensland.

In contrast, the Warriku (Warrego) catchment drains more arid and flat areas to the north of the Selected Area. The Warriku River only flows intermittently during periods of high rainfall in its upper catchment, usually manifesting downstream as slow-moving freshes and floods. Within the Selected Area, the Warriku River winds its way south to the Baaka River. It is bordered to the west by an extensive floodplain system known as the Western Floodplain (Figure 2).

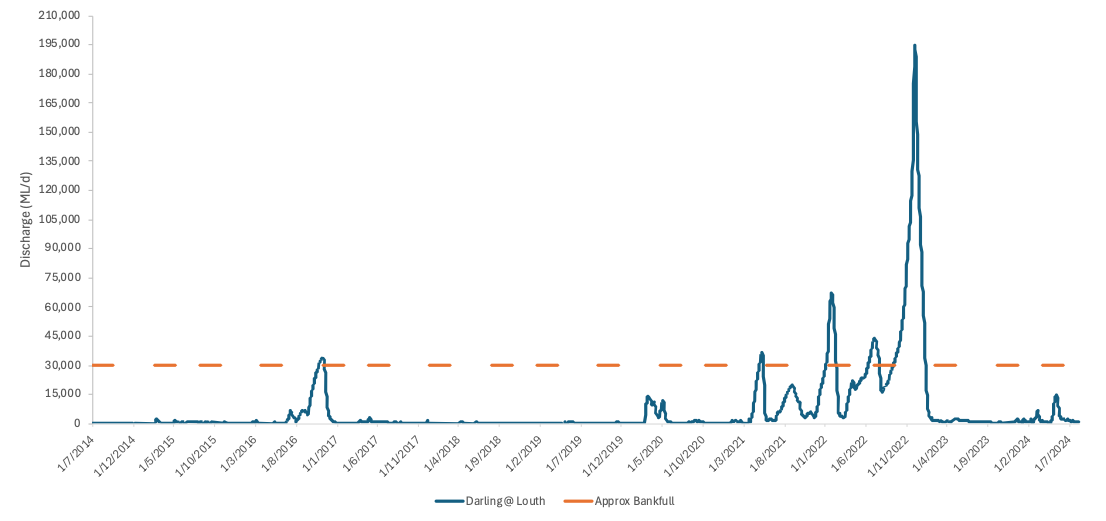

The CEWH implemented the Long-term Intervention Monitoring (LTIM; 2014-2019) and the Flow-MER (2019-2024) programs in this area to evaluate the outcomes of Commonwealth water for the environment delivery. This story explores some key learnings since monitoring began in the Warrego-Darling Selected Area spanning times of severe drought (2018-20) to significant floods (2021-22; Figure 2).

From 2014 to late 2019 conditions were generally dry and water quality tended to suffer due to lack of flow resulting in disconnected pools and channels. Occasional rainfall promoted small natural flows and Commonwealth water for the environment releases supported some frog and fish recruitment before drought conditions reached extremes in 2017-2019 (Figure 3). In this period the Warriku and Western Floodplains disconnected completely, and monitoring saw a transition in floodplain vegetation from a wet phase to a dry phase, with terrestrial species taking over.

Engagement with local First Nations peoples began in 2019 with collaboration on stories and has grown since then. The Kurnu-Baakandji People who are the Traditional Owners of the Warriku and Baaka Rivers have helped to inform our researchers of local knowledge and practices (Figure 4). Incorporating knowledge, such as traditional Paakantyi language in works continues to help in communicating the stories of this region.

Beginning in 2021, significant flows caused inundation across the Selected Area (Figure 6). Commonwealth water for the environment management helped to extend this inundation into 2023. The Western Floodplain shifted back to a wet state and biodiversity boomed. These favourable conditions sustained the growth of wirnta (lignum; Figure 7) and coolibah seedlings and saplings and promoted coolibah and blackbox flowering and seed development. Hyrtl’s tandan catfish (Figure 6) were observed at their highest abundance since 2016. Waterbird species richness, density and diversity was increased. Murray River turtle hatchlings were observed in Boera Dam in February 2023.

However, despite the wet conditions it was not all good news. Native fish species such as Murray cod and silver perch, which are expected to exist and flourish in the Selected Area, are in such small numbers that sampling efforts could not detected individuals on a regular basis. For these species to occupy the reaches of the Selected Area once again, re-stocking in combination with habitat restoration and good flow conditions will be needed.

The 2023-24 water year began with dry conditions which persisted until late February 2024. Water quality was especially poor in early 2024, with some monitoring sites having algal blooms with many sites having high water temperatures and low dissolved oxygen. These conditions improved following the commencement of a sustained flow through the Area in January 2024, and heavy rainfalls in April and May 2024. Resulting inundation made some sites inaccessible for the Autumn surveys. Fish surveys saw the capture of some significant species, including 100-200 mm long golden perch and Hyrtl’s tandan in the Warriku.

The Selected Area has displayed distinctive wet and dry phases over the decade of monitoring. Throughout each phase, informed water for the environment releases helped maintain or extend hydrological connectivity between the Warriku and Baaka Rivers and the Western Floodplain. In doing so, these releases benefitted various flora and fauna species (Figure 8 and 9).

These learnings about the ecological processes occurring in the Junction of the Warrego and Darling Rivers Selected Area and how water for the environment can be used to aid these processes will inform continued adaptive management.

Managing water for the environment is a collective and collaborative effort, working in partnership with communities, private landholders, scientists and government agencies – these contributions are gratefully acknowledged.

We acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the land on which we live, work and play. We also pay our respects to Elders past, present and emerging.