Traditional Gamilaaraay Language of the Gomeroi nation used in this article (H. White & B. Duncan – Speaking Our Way, M. Mckemey).

The Commonwealth Environmental Water Holder’s (CEWH) Science Program funds the Flow Monitoring, Evaluation and Research (Flow–MER).

Did you know that there are over 300 species of Marranii-maa (dragonfly) in Australia? These species are divided into eight families, two of which (Hemicorduliidae and Aeshnidae) occur within the Gwydir Wetlands State Conservation Area. During the nine years of the Long Term Intervention Monitoring Project and Flow-MER program, we have studied these Marranii-maa as part of the food web. Marranii-maa depend on water (gali) to fulfil their lifecycle and make up a very important part of wetland ecosystems.

Within wetlands, Marranii-maa are both prey and predator. Young and adults alike eat other smaller insects (gawu) and fish fry, while they themselves are prey for larger creatures such as birds, frogs, fish, and sometimes other larger insects. Marranii-maa are usually the apex predator in the insect world. With incredible flight capabilities and an almost 360-degree vision, they are very efficient hunters.

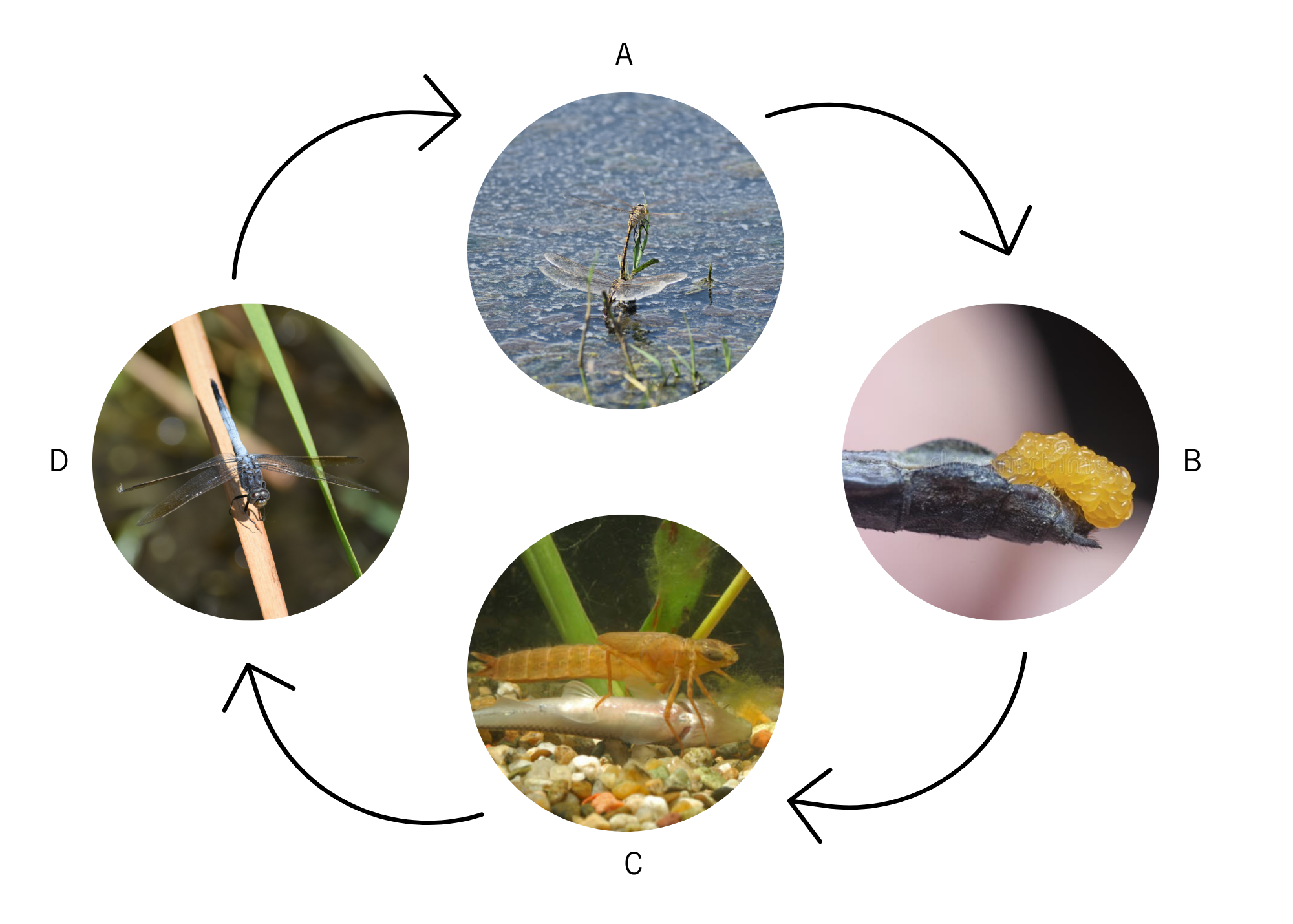

Marranii-maa are an opportunistic species; with a short life cycle of 8-10 week in which they have three stages in life: egg – larva – adult. We most often see the adults, with their vibrant wings and quick movements across water.

The Lifecycle

Egg (gawu) – This stage of the lifecycle is aquatic. In the water, females deposit eggs into plant tissue or into the mud where they remain until hatching after one to five weeks.

Larvae – Marranii-maa larvae, also named nymphs, vaguely resemble their adult counter parts. Usually aquatic, they are quite dull in colour with six legs, large eyes and slightly long, chunky bodies. Nymphs are carnivorous and in their aquatic habitat employ either ‘sit and wait’ or ‘attack’ hunting strategies, snapping up other small aquatic animals as their prey. As larvae, they undergo several stages of growth and when fully developed will move to an exposed log or rock to undergo the final stage of metamorphosis. Once perched in the open air the larval skin splits and after an hour has passed, the adult dragonfly emerges.

Adult – Newly emerged adult Marranii-maa stretch out their wings to dry before flying away from their aquatic nursery. Young adult dragonflies reach sexual maturity after about one month.

Male Marranii-maa are territorial, perching on branches or other objects to patrol their surroundings and drive away rival males. They make many attempts to mate with females until one finally accepts the offer. When accepted, the male will attach the back of his abdomen to the female’s head and in this position they fly together. They then find a perch and proceed to mate. The female will locate a suitable waterbody and lay her eggs in or near the water, completing the life cycle.

As with all aquatic dependent species, Marranii-maa need water to complete their lifecycle. In the 2019-20 water year conditions remained very dry (balal). A combination of Commonwealth and State managed water for the environment was delivered to the lower Gwydir system in November to January to support the wetlands. As areas, such as the Gingham Waterhole, rewetted in early 2020, insects (gawu) including Marranii-maa nymphs were more widespread in the Gingham Watercourse during April 2020 than previously, indicating the egg banks survived the preceding dry period and burst into life following inundation.

Managing water for the environment is a collective and collaborative effort, working in partnership with communities, private landholders, scientists and government agencies – these contributions are gratefully acknowledged.

We acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the land on which we live, work and play. We also pay our respects to Elders past, present and emerging.